7:00 – 3:00 ASRC MKT

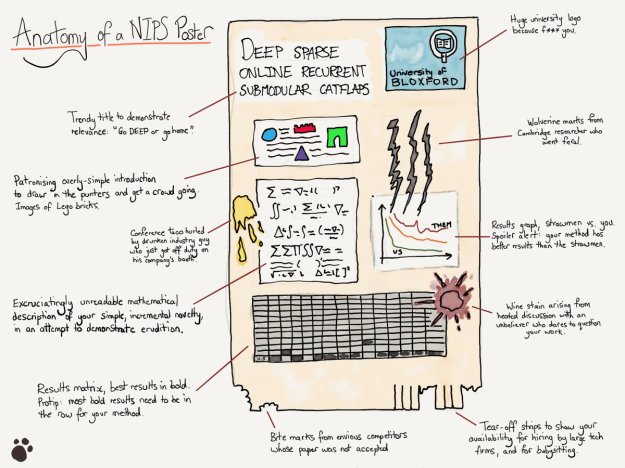

- Machine learning art gallery from NIPS this year:

- I’m reading this article on the prehistory of Bitcoin, and am realizing that there are several implications for ensuring immutability of data. For example, the entire set of records could be hashed to produce a unique has that would be disrupted if any of the records were altered.

- Continuing Schooling as a strategy for taxis in a noisy environment here. Done! Promoted to Phlog

- Still collecting data for web access times at work. Average time to open/finish loading a page is something around 5 seconds at work, 2 seconds at home.

- Neural correlates of causal power judgments

- Denise Dellarosa Cummins

- Causal inference is a fundamental component of cognition and perception. Probabilistic theories of causal judgment (most notably causal Bayes networks) derive causal judgments using metrics that integrate contingency information. But human estimates typically diverge from these normative predictions. This is because human causal power judgments are typically strongly influenced by beliefs concerning underlying causal mechanisms, and because of the way knowledge is retrieved from human memory during the judgment process. Neuroimaging studies indicate that the brain distinguishes causal events from mere covariation, and also distinguishes between perceived and inferred causality. Areas involved in error prediction are also activated, implying automatic activation of possible exception cases during causal decision-making.

- Writing up the Academic scenario

3:00 – 4:00 Fika – end of semester shindig

4:00 – 6:00 Meeting w/Wayne

- Basically a status report. Maybe look at computational ecology journals if CHIIR falls through in a bad way

- Look at workshops as well – Max Plank could be fun

- Workshopped a workshop title with Wayne and Shimei

You must be logged in to post a comment.